I was proud of my family's contribution to the World War 1 exhibition at Kings Heath Primary school this weekend, as well as my family, on both sides of the trenches. Here's what Jago wrote, and also a fabulous section translated from Heinrich Hoenen's book at bottom:

|

| George (left), with Arthur (middle, Grandma’s Dad) & Minty |

‘Great Great Uncle George was killed during the First world war. There was George, Minty, Arthur and Fred’

[George is in the photo below (left), with Arthur (middle, Grandma’s Dad) & Minty]

‘George was the eldest, loved by the younger children. My Dad, your great Grandad, said he was a lovely caring man, and they really missed him when he went to war.’

‘He was killed towards the end of the war when he was eighteen in October 1918, which was really sad. He went when he was really younger - probably about 17. He shouldn’t have gone so early but he did. He was killed in a battle, a small battle. The grave where he is buried is in the middle of a field in a farm in France and there are only a hundred graves there, and they were all the people who were killed there at the same time.’

My Great Great Grandfather Heinrich Hoenen fought for Germany and was a very brave horseman. He got the ‘Iron Cross’ for bravery rescuing injured soldiers when he wasn’t supposed to (My Grandmother has translated my great great grandfather’s story of how he got the Iron Cross)

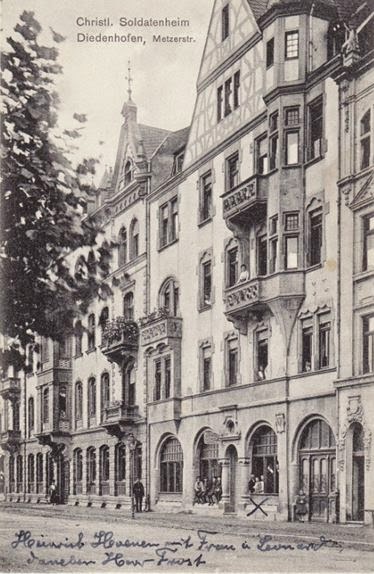

At the end of the war he had to give up his house [see photo left] and most of his things were left in France because Metz was now part of France.

Photo below is of Heinrich Hoenen (with his Iron Cross tucked into his jacket) with my Great Grandfather behind him (far left).

From Great-great-grandfather’s records, a booklet entitled ‘The Guiding Hand’ Chapter 25

(Heinrich Hoenen: Die treue Hand, Second Extended Edition):

On 1 September 1914 I received the order to accompany 10 waggon-loads of ammunition to the front line. When checking the maps, I found them very poor and incomplete and, as we moved uphill through dense forest, the roads were in a terrible state due to heavy rainfall on the previous days, so that our waggons loaded with heavy ammunition at times sank right up to their shafts. My men had to work very hard to get the waggons to their destination. The unloading of the ammunition was quickly done, and we were all looking forward to returning back to base.

At this moment the Artillery Captain took me to one side and said: ‘’Take your waggons down to the river Meuse and follow it to Dun. Take on board as many wounded soldiers as you can, and move on to the nearest field hospital at Damvillers.’’

I have to obey.

Down by the river the battle is raging – explosions and burning houses light up the night, shells whistle by and grenades detonate all around. Our horses are terrified and difficult to control, my men are frightened out of their wits and lose their self-control.

My heart is pounding in my chest, I too have a wife and children at home, my mouth is dry. I pray not to lose my courage, and for God to look after my loved ones if I should be killed. I feel strengthened by the prayer and am able to give clear orders, my men obey my commands.

The waggons approach one by one. I accompany the gunners to look for the wounded among the dead and dying. We lift the wounded onto the waggons as gently as we can and lay them on the straw. We give First Aid, bandaging wounds and injuries, and so it goes on, one waggon after the other, until they are all laden and can take no more, wishing there was more we could do.

However, we must get back to base with the ones we have on board, about 50 in all, so that they can be treated. One waggon after the other is leaving now and stopping on the road to Damvillers. Just as I mount my horse and give the order to leave, my horse suddenly collapses. A piece of shrapnel has hit it in the body, just missing my knee and taking off a corner of my uniform. I quickly unhitch the lead-horse from one of the waggons and swing myself onto it. We move off at a moderate speed so as not to shake up the poor people we are carrying. They cannot help but cry out in the dark as we get further away from this place of horror.

Now we are on a safer road and in the east the day is dawning. It’s still a long way to Damvillers. I ride up to this waggon or that and try to give encouragement. In one of them lies a Major, who has a bullet stuck in his back. He asks me for a light so he can smoke a cigarette to dull the pain. A Lieutenant asks me to stop – he is not as badly wounded as his comrades beside him, and wants to walk to give them more room. He has had his hand shot off, and bravely walks behind the waggon.

Eventually we arrive in Damvillers and can deliver our charges to the field hospital. The wounded Major asks me for my name and unit and writes the answers in his notebook. I cannot imagine why he does that. And now we must get on again. We have no time to lose and will have to load up the waggons with ammunition before we return to our unit. We have not eaten since lunchtime yesterday and my men are not happy. After loading up at the ammunition depot at Jametz we feed our horses and have some food from our own supplies.

But our problems are not behind us yet. When we get back to the camp where our unit had been the day before, we find them gone. After a lot of searching we finally meet up with them the next day, and I report to my Commander. Instead of the expected praise, I am reprimanded because I carried out an order that had not been part of our own regulations. I should have refused the order to take the wounded to the field hospital. Our job is not to transport the wounded, but to get ammunition to the battlefield. The medical units are responsible for the wounded. I remained calm, but I am quite sure that, in the same situation, I would have done exactly the same again.

Weeks went by, Christmas arrived. On Christmas Day, the General of the Artillery arrived with his Adjutants. Why was he here?

I am busy in the small village church where our quarters are, making preparations for the Christmas celebrations that afternoon. Suddenly I am called and have no idea why.

Outside the unit is drawn up on parade. I take my place. The Artillery General marches along slowly. Our Commander reports to him. The Adjutant hands a small package to the General whilst we are all extremely curious. Then the General slowly approaches and comes to a stop in front of me, raising his voice he says:

“In the name of His Imperial Highness, the Crown Prince, Commander of the 5th Army, the Iron Cross 2nd Class is awarded to the NCO Heinrich Hoenen for bravery in front of the enemy.” Whereupon he pins the medal onto my chest and shakes my hand. My comrades burst out into a loud cheer.

I leant later that a Major M. whom I had picked up from the battlefield along with other wounded on the night from the 1st to the 2nd September, had reported the event to High Command. I assume that it was the Major who had asked for my name and unit on that occasion.

The award was a great honour to me. But I was not entirely happy as all those comrades who had helped me on that night would have deserved the same honour. Even today, when I am wearing the ribbon in my buttonhole, I wear it as a representative of all those who on that day risked their lives to save their fellow soldiers.

Heinrich Hoenen was orphaned at an early age and cared for by foster parents. The head of his new family was a master saddler, and so great-great-grandfather was taken on as an apprentice saddler.

Later he joined the Dragoons (soldiers on horseback) for his compulsory Military Service at the turn of the century. He was trained as a dispatch rider, probably because of his previous experience with horses, saddles and harnesses. At that time there were no cars or lorries, and all transport was horse-drawn, apart from trains.

As a dispatch rider his job was to carry messages from Headquarters to the front line, for which he needed to be able to read maps.